Cancer Survivors: What are Their Concerns and Quality of Life Across the Survivorship Trajectory?

Article Information

Gek Phin Chua1*, Quan Sing Ng2, Hiang Khoon Tan3, Whee Sze Ong4

1CEIS (Research & Data), National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore

2Division of Medical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore

3Division of Surgery and Surgical Oncology, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore

4Division of Clinical Trails and Epidemiological Sciences, National Cancer Centre Singapore, Singapore

*Corresponding Authors: Gek Phin Chua, 11 Hospital Crescent, Singapore 169610, Singapore

Received: 15 March 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2021; Published: 01 April 2021

Citation:

Gek Phin Chua, Quan Sing Ng, Hiang Khoon Tan, Whee Sze Ong. Cancer Survivors: What are Their Concerns and Quality of Life Across the Survivorship Trajectory?. Journal of Cancer Science and Clinical Therapeutics 5 (2021): 166-196.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Purpose: Survivors of cancer deal with a myriad of acute, chronic, and late effects of cancer and its treatment which can linger on for decades and inadvertently affect their quality of life (QOL). The aim of this study is to determine the main concerns of survivors at various stages of the cancer survivorship, and to assess whether these concerns have any effect on their QOL.

Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on cancer survivors diagnosed with colorectal, breast, lung, gynaecological, prostate or liver cancers (top 6 cancers in Singapore) who were seen at the National Cancer Centre Singapore between 11 April and 12 July 2017. Eligible study participants self-completed a questionnaire adapted from the Mayo Clinic Cancer Centre’s Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs. QOL was rated by participants on a scale of 0-10, with higher ratings denoting higher level of QOL.

Results: A total of 1107 cancer survivors filled in the questionnaire. The top 5 concerns among all survivors were cancer treatment and recurrence risk (51%), followed by long-term treatment effects (49%), fear of recurrence (47%), financial concerns (37%) and fatigue (37%). Cancer treatment and recurrence risk, long-term treatment effects and fear of recurrence were amongst the top concerns across the survivorship trajectory. Mean QOL was 7.3 on a scale of 0-10. Completed treatment patients had higher QOL score than the newly diagnosed and on treatment patients and the patients dealing with recurrence or second cancer patients. Predictors for QOL included the economic status and housing type of patients and whether patients were concerned with pain and fatigue.

Conclusion: This study reveals that cancer survivors in Singapore face multiple challenges and had various concerns at variou

Keywords

Cancer Survivors; Concerns; Financial Support; Quality of Life; Survivorship; Fatigue; Pain

Cancer Survivors articles; Concerns articles; Financial Support articles; Quality of Life articles; Survivorship articles; Fatigue articles; Pain articles

Cancer Survivors articles Cancer Survivors Research articles Cancer Survivors review articles Cancer Survivors PubMed articles Cancer Survivors PubMed Central articles Cancer Survivors 2023 articles Cancer Survivors 2024 articles Cancer Survivors Scopus articles Cancer Survivors impact factor journals Cancer Survivors Scopus journals Cancer Survivors PubMed journals Cancer Survivors medical journals Cancer Survivors free journals Cancer Survivors best journals Cancer Survivors top journals Cancer Survivors free medical journals Cancer Survivors famous journals Cancer Survivors Google Scholar indexed journals Concerns articles Concerns Research articles Concerns review articles Concerns PubMed articles Concerns PubMed Central articles Concerns 2023 articles Concerns 2024 articles Concerns Scopus articles Concerns impact factor journals Concerns Scopus journals Concerns PubMed journals Concerns medical journals Concerns free journals Concerns best journals Concerns top journals Concerns free medical journals Concerns famous journals Concerns Google Scholar indexed journals Financial Support articles Financial Support Research articles Financial Support review articles Financial Support PubMed articles Financial Support PubMed Central articles Financial Support 2023 articles Financial Support 2024 articles Financial Support Scopus articles Financial Support impact factor journals Financial Support Scopus journals Financial Support PubMed journals Financial Support medical journals Financial Support free journals Financial Support best journals Financial Support top journals Financial Support free medical journals Financial Support famous journals Financial Support Google Scholar indexed journals Quality of Life articles Quality of Life Research articles Quality of Life review articles Quality of Life PubMed articles Quality of Life PubMed Central articles Quality of Life 2023 articles Quality of Life 2024 articles Quality of Life Scopus articles Quality of Life impact factor journals Quality of Life Scopus journals Quality of Life PubMed journals Quality of Life medical journals Quality of Life free journals Quality of Life best journals Quality of Life top journals Quality of Life free medical journals Quality of Life famous journals Quality of Life Google Scholar indexed journals Survivorship articles Survivorship Research articles Survivorship review articles Survivorship PubMed articles Survivorship PubMed Central articles Survivorship 2023 articles Survivorship 2024 articles Survivorship Scopus articles Survivorship impact factor journals Survivorship Scopus journals Survivorship PubMed journals Survivorship medical journals Survivorship free journals Survivorship best journals Survivorship top journals Survivorship free medical journals Survivorship famous journals Survivorship Google Scholar indexed journals Fatigue articles Fatigue Research articles Fatigue review articles Fatigue PubMed articles Fatigue PubMed Central articles Fatigue 2023 articles Fatigue 2024 articles Fatigue Scopus articles Fatigue impact factor journals Fatigue Scopus journals Fatigue PubMed journals Fatigue medical journals Fatigue free journals Fatigue best journals Fatigue top journals Fatigue free medical journals Fatigue famous journals Fatigue Google Scholar indexed journals Pain articles Pain Research articles Pain review articles Pain PubMed articles Pain PubMed Central articles Pain 2023 articles Pain 2024 articles Pain Scopus articles Pain impact factor journals Pain Scopus journals Pain PubMed journals Pain medical journals Pain free journals Pain best journals Pain top journals Pain free medical journals Pain famous journals Pain Google Scholar indexed journals gynaecological articles gynaecological Research articles gynaecological review articles gynaecological PubMed articles gynaecological PubMed Central articles gynaecological 2023 articles gynaecological 2024 articles gynaecological Scopus articles gynaecological impact factor journals gynaecological Scopus journals gynaecological PubMed journals gynaecological medical journals gynaecological free journals gynaecological best journals gynaecological top journals gynaecological free medical journals gynaecological famous journals gynaecological Google Scholar indexed journals cancer treatment articles cancer treatment Research articles cancer treatment review articles cancer treatment PubMed articles cancer treatment PubMed Central articles cancer treatment 2023 articles cancer treatment 2024 articles cancer treatment Scopus articles cancer treatment impact factor journals cancer treatment Scopus journals cancer treatment PubMed journals cancer treatment medical journals cancer treatment free journals cancer treatment best journals cancer treatment top journals cancer treatment free medical journals cancer treatment famous journals cancer treatment Google Scholar indexed journals cancer survivors articles cancer survivors Research articles cancer survivors review articles cancer survivors PubMed articles cancer survivors PubMed Central articles cancer survivors 2023 articles cancer survivors 2024 articles cancer survivors Scopus articles cancer survivors impact factor journals cancer survivors Scopus journals cancer survivors PubMed journals cancer survivors medical journals cancer survivors free journals cancer survivors best journals cancer survivors top journals cancer survivors free medical journals cancer survivors famous journals cancer survivors Google Scholar indexed journals

Article Details

Abbreviations:

NCCS: National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship; QOL: Quality of Life; NT: Newly diagnosed and on treatment; CT: Completed treatment or were cancer-free ≥5 years; RS: Recurrence or second cancer; SD: Standard deviation; FOR: Fear of recurrence; HRQOL: Health-related Quality of Life; SCP: Survivorship Care Plan; IOM: Institute of Medicine

1. Introduction

The advent of technologies in the early detection and diagnosis of cancer with better treatment modalities and care have improved the survival rates of many cancer patients [1]. There are many definitions of cancer survivors. The biomedical definition of cancer survival refers to a population of cancer patients who live disease-free for at least 5 years after treatment. In contrast, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS) defines it as an individual from the time of cancer diagnosis through the balance of his or her life [2]. Cancer survivors experience high level of physical, emotional, and social problems related to their cancer and treatment [3-7]. Besides the short-term adverse effects, cancer treatment can also cause long-term (late) health effects. Late effects of cancer treatment include, but not limited to pain, chronic fatigue, lymphedema, peripheral neuropathy, cognitive impairment, infertility, cardiomyopathy, osteoporosis, including an increased risk of second primary cancers [8-13]. Cancer survivors also experienced persistent emotional and psychological issues relating to anxiety, depression, fears of recurrence and concerns regarding passing the disease to their offspring [14, 15]. They also face a host of economic, financial, insurance and employment concerns [10, 15, 16]. These studies suggest that long-term consequences of cancer include not only lingering issues that present after diagnosis and treatment, but also new concerns that develop over time. These effects can affect day-to-day functioning and coping of cancer survivors and inadvertently affect their quality of life (QOL). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines QOL as an individual’s perception of life, goals, expectations, standards and concerns in the context of culture and value systems [17]. A number of illness-related factors can affect QOL. In the context of cancer survivors, side effects of cancer and its treatment [11, 12, 18], financial concerns [16, 19], distress over recurrence [19], family-related distress [19] have been found to affect survivors’ QOL. It is an important predictor in outcomes of the disease and its treatment [20] and one of the indicators of adjustment in cancer survivors [12]. It is therefore crucial to understand and address not only the immediate but also the long-term medical and psychosocial issues that confront cancer survivors as they transition across the survivorship trajectory in order to enhance coping skills and improve their QOL.

The importance of identifying the most salient concerns the cancer survivors are experiencing in order to guide practice is a fundamental component of patient-centered care. According to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) [21], besides effective patient education, empowerment, and communication, patient-centered care in the oncology setting also includes coordination and integration of care; and provision of emotional support as needed, such as relieving fear and anxiety and addressing mental health issues. Ascertaining the concerns of cancer survivors would aid healthcare professionals with timely and appropriate information in addition to developing interventions to better address and manage survivors’ concerns. This could potentially enhance survivors’ coping skills, alleviate survivors’ psychologic distress about these concerns, improve satisfaction with care delivery, and exert a positive effect on their QOL [22, 23]. Although cancer is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Singapore [24], there are no studies reporting on the concerns of cancer survivors in Singapore. Therefore, the generalizability of outside studies on how to address the survivors’ concerns and improve delivery of survivorship care to the Singapore healthcare system is limited. Furthermore, limiting generalizability is the small sample size [25], a focus on cancer types [10, 11, 26, 27] and age [28-30] of previous studies in their application to Singapore.

The primary aim of this study is to establish the main concerns of cancer survivors across the cancer trajectory, and the secondary aim is to assess whether these concerns have any effect on their QOL. The overall goal was to use the insights from the study to guide practice on patient care.

2. Methods

2.1 Study Design and Participants

A cross-sectional survey was conducted at the specialist outpatient clinics and the clinics at the radiation oncology department in the National Cancer Centre Singapore, which sees the majority of the public sector oncology cases in Singapore [31]. All eligible patients were invited to take part in the survey during their first visit to the cancer center from 11 April to 12 July 2017. Inclusion criteria of this study were cancer survivors who were defined as individuals from the time of cancer diagnosis through the balance of their lifespan according to the NCCS, aged at least 21 years old, able to read and write English or Chinese, did not have major intellectual or psychiatric impairment, and diagnosed with either colorectal, breast, lung, gynaecological, prostate or liver cancer (the top 6 cancers in Singapore).

2.2 Instruments

The self-administered questionnaire used in the survey was based on the “Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs” developed by the Mayo Clinic Cancer Centre [32]. The instrument was developed based on extensive literature reviews and pilot tested. Content validity was established through review by members of the Cancer Education Network. The questionnaire was translated to Chinese and verified by two staff who were competent in both English and Chinese languages. Five domains of concerns were covered in the questionnaire viz. (1) physical (20 issues), (2) emotional (14 issues), (3) social (7 issues), (4) spiritual (4 issues), and (5) others (6 issues). The issues covered in each domain were the same as those in the original survey from the Mayo clinic, except for the additional of one issue on “Cancer treatment and recurrence risk” under the others domain. Respondents assessed the level of concern on each issue in the past 1 week prior to the survey using a 5-point Likert scale (Not concerned, Not really concerned, Neither unconcerned nor concerned, Concerned and Very concerned). The questionnaire also contained open-ended questions where respondents were asked to share on their primary source of strength during their cancer experience and what was their primary concern regarding their healthcare needs. In addition, similar to the Mayo clinic’s original survey, respondents also rated their overall QOL in the past 1 week prior to the survey from 0 (as bad as it can be) to 10 (as good as it can be). Demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status), socioeconomic (education qualification, economic status, housing type), clinical (cancer type, year since diagnosis) and treatment characteristics were also collected as part of the questionnaire.

2.3 Study Procedure and Data Collection

Prior to each patient’s first clinic visit during the survey period, research assistants reviewed the patient’s medical records and performed pre-screening. A copy of the survey form together with an explanatory note containing detailed explanation of the study purpose and procedure on how to complete the questionnaire were attached to the patient’s medical case sheet for each potential eligible patient. The clerical staff of the clinics in the cancer center confirmed the eligibility criteria of each patient and invited only those eligible to participate. Participation in the survey was voluntary and completion of the survey form indicated patient’s consent to participate in the study.

2.4 Ethics and Consent to Participate

Ethical consent was obtained from the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) prior to the study. Waiver of written informed consent was obtained as no personal identifiers of respondents were obtained.

2.5 Data Analysis

Data were analysed for the study participants according to cancer survivorship stages. The cancer survivorship stages included in these further analyses were selected and grouped based on the clinical significance and the number of patients in the stage: patients who were newly diagnosed and on treatment (NT), patients who had completed treatment or were cancer-free ≥5 years (CT), and patients dealing with recurrence or second cancer (RS). Patient characteristics at baseline were summarized as median (interquartile range) or frequency (percentage). Differences in mean QOL score between 2 groups of patients were compared using independent T-tests. Logistic regression models were fitted to assess the association of various variables with patients reporting ≥ 1 concerned or very concerned. Linear regression models were fitted to identify the variables associated with QOL. Statistically significant variables with p<0.05 in the univariate analyses were entered into the multivariable regression analyses. Model diagnostics were performed in which spearman correlations were used to identify potential multicollinearity between independent variables. Graphical assessments were made to check linear relationship between the variables included in each model with either the log odds of patients reporting ≥ 1 concerned or very concerned issue (for logistic model) or QOL (for linear model), as well as the normality and homoscedasticity of residuals of each linear model. All reported p-values were 2-sided, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 [33].

3. Results

3.1 Patient Characteristics

A total of 1107 patients filled in the survey, of which 248 were NT (22%), 687 were CT (62%) and 96 were RS (8.7%). Median age of all patients was 61 years (range, 21-89 years) and two-thirds were female (Table 1). The majority of the patients were married (75%), had secondary and higher qualifications (received at least 10 years of basic education) (78%), and were either employed (43%) or retired (34%). Patients across the cancer survivorship stages were similar in these characteristics. The most common cancer site was the breast (40%), followed by colorectal (22%) and lung (14%). Compared with the CT and RS patients, there were proportionately fewer breast cancers (32% NT vs 43% CT vs 42% RS) and more lung cancers (22% NT vs 10% CT vs 12% RS) amongst the NT patients.

3.2 Concerns

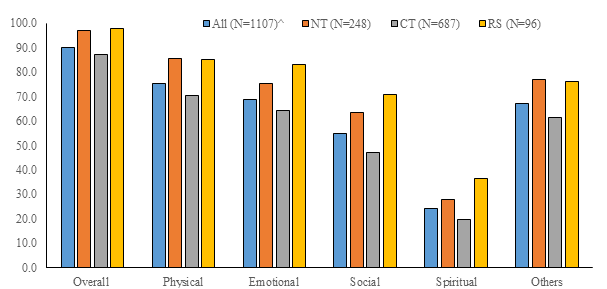

About 90% of the study participants reported that they had at least one issue of concern (Figure 1). Based on the study participants, the issue with the highest percentage of patients reporting that they were concerned or very concerned with was cancer treatment and risk of recurrence (51%), followed by long-term treatment effects (49%), fear of recurrence (FOR) (47%), fatigue (37%) and financial concerns (37%) (Additional Table 1). Prevalent concerns that were found to be common across the cancer survivorship stages included cancer treatment and recurrence risk, long-term treatment effects and FOR were amongst the top 5 concerns reported by patients. CT and RS patients who had received cancer treatment previously were also highly concerned with fatigue, while NT and RS patients who were either currently undergoing or going to receive treatment were highly concerned about their finances. In addition, NT and CT patients were also highly concerned with keeping their primary care physician informed of their cancer treatment and recurrence risk. When patients were broken down by various patient characteristics within each cancer survivorship stage, the most prevalent concern reported by patients in each characteristic subgroup remained largely the same as that reported by all the patients in the survivorship stage (data not shown).

3.3 Risk Factors for Reporting At Least One Issue of Concern

Risk factors for patients to report at least one issue of concern were listed in Table 2. RS patients were more likely than CT patients to report at least one issue of concern overall and in each domain. Patients who had chemotherapy were also more likely to report at least one issue of concern in each of the non-spiritual domain (i.e. physical, emotional, social and others). Notably, tumour type was not a significant predictor for presence of at least one issue of concern amongst patients in this study.

3.4 Quality of Life

The overall mean QOL score was 7.3 with a standard deviation (SD) of 2.1. CT patients had higher QOL score (mean ± SD: 7.6 ± 1.9) than the NT patients (6.9 ± 2.2) and the RS patients (6.7 ± 2.5). The mean QOL scores of patients who had concerns in each of the non-spiritual domains were significantly lower than those of their counterparts who were not concerned (Table 3). On multivariable linear regression analysis, predictors for QOL included the economic status and housing type of patients and whether patients were concerned with pain and fatigue (Table 4). Patients who had pain and fatigue concerns reported QOL scores that were about 1 point lower than those who did not have such concerns. Significant difference in QOL was also found between patients who were concerned with the most prevalent issue and those who were not for the NT and RS patients, but not the CT patients (Additional Table 2). Cancer survivorship stages were not independently associated with QOL.

3.5 Primary Source of Strength

Cancer survivors relied mainly on their family members for strength to cope with the various concerns that they had with their disease. Around 53% of all cancer survivors reported family as their primary source of health of strength during their cancer experience (Additional Table 3). This reliance on the family was higher amongst the RS patients (66%) than the NT (51%) and CT (52%) patients. Besides family, other common sources of strengths for cancer survivors included themselves (18%), religion (15%) and friends (13%).

NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS-had recurrence/second cancer; ^ Includes patients on palliative care; * Among patients with non-missing values

Table 1: Patient characteristics by cancer survivorship stage.

Figure 1: Patients with at least one issue of concern by domain and cancer survivorship stage.

NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS-had recurrence/second cancer; ^ Includes patients on palliative care

NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS-had recurrence/second cancer; ^ Includes patients on palliative care; * Tie with at least one other issue within the patient cohort; # New question added to the original questionnaire from Mayo clinic

Additional Table 1: Patients who were concerned or very concerned on each issue of concern by cancer survivorship stage.

OR-odds ratio; CI-confidence interval; NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS- had recurrence/second cancer

Table 2: Multivariable logistic regression for the presence of at least one issue of concern in domain.

QOL-quality of life; SD-standard deviation; NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS-had recurrence/second cancer; C-patients with at least one issue of concern in domain; NC-patients with no issue of concern in domain; ^ Includes patients on palliative care; * 0.01≤p<0.05; **0.001≤p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Table 3: Comparison of QOL scores by whether patients had at least one issue of concern in domain and cancer survivorship stage.

QOL-quality of life; SE-standard error; C-concerned or very concerned with issue; NC-not concerned, not really concerned or neither concerned nor unconcerned with issue; ^ Excludes 3 students from analysis as this small category of patients cannot be combined with the other categories of economic status appropriately

Table 4: Multivariable linear regression for QOL score.

QOL-quality of life; SD-standard deviation; NT-newly diagnosed, on treatment; CT-completed treatment/cancer-free ≥ 5 years; RS-had recurrence/second cancer; C-patients who were concerned or very concerned with issue; NC-patients who were not concerned, not really concerned or neither concerned nor unconcerned with issue; ^ Includes patients on palliative care; # See Additional Table 1 for the full description of each issue; * 0.01≤p<0.05; **0.001≤p<0.01; ***p<0.001

Additional Table 2: Comparison of QOL scores by whether patients were concerned or very concerned with the issue of concern and cancer survivorship stage.

^ Includes patients on palliative care

Additional Table 3: Primary source of strength during cancer experience.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the concerns of cancer survivors across the cancer trajectory in Singapore. The present research adds to the body of knowledge that is currently lacking in Singapore. It also contributes to the goal of developing a patient-centered information and support system to assist the cancer survivors across the cancer trajectory. Singapore, a young nation state has attained a high standard of health with an average life expectancy at birth for males at 81 years and 85.4 years for females [34]. Early detection and better treatment modalities have resulted in a significant increase in survival rates. For instance, the 5-year survival rate for breast cancer has increased from 67.5% during the period 2005-2009 to 79.5% during the period 2008-2012 [35]. Even though cancer has been the leading cause of mobility and mortality for four decades, unlike most developed nations, cancer survivorship care is in its infancy stage. The majority of cancer care is provided mainly through the 2 publicly funded national cancer centres. Over the years, efforts were made to provide cancer rehabilitative and supportive programs, such as speech therapy for survivors affected by head and neck cancers, and support groups for breast cancer survivors. However, these programs being limited in scope and range are unable to address the comprehensive survivorship care needs of all cancer survivors. As such, knowledge on the concerns of cancer survivors and their effects on QOL is an important step in developing evidence-based interventions to enhance coping skills and improve survivors’ QOL.

In this study, we found that the top concerns of the cancer survivors were cancer treatment and the risk of recurrence, long-term treatment effects and FOR. Cancer treatment related acute and late side effects have been well reported in the literature [3, 5, 8-12, 14, 15]. It has also been reported that even 20 years after stopping cancer treatment, the risks of recurrence (distant or contralateral breast) were present [36]. In our study, FOR was the top emotional concern among the cancer survivors and also throughout the cancer trajectory. This finding has also been reported by other studies [14, 25, 37-42]. Evidence in literature reveals the negative impacts associated with FOR, including emotional distress [43], functional status [44] and QOL [44-46]. Unlike other studies, we find that higher FOR is not associated with poorer QOL of survivors. A recent study by Cho and Park [47] on 292 adolescent and young adult cancer survivors found that the negative association between FOR and mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was moderated by perceived growth (such as relating to others, personal growth, new possibilities, appreciation of life and spiritual life). In view of the moderating effects of perceived growth on the FOR-HRQOL links, enhancing on the growth perception may also be a strategy worth considering. As our study only measured the respondents’ overall QOL and we did not measure the perceived growth, this finding warrants further study.

Financial concerns were amongst the top concerns for patients who were either undergoing or about to undergo treatment in this study. We also found that those with lower economic status including those staying in public Housing Development Board (HDB) flats are at higher risk of poorer QOL. As demonstrated in other studies, financial burden of cancer treatment is high and respondents expressed a great deal of worry about financial matters [42, 49, 50]. Evidence [50] also indicates that increased financial burden as a result of cancer care costs is the strongest independent predictor of poor QOL and adverse psychological issues such as depression, anxiety, and distress [50, 51] among cancer survivors. As QOL is negatively affected by financial burden, early identification of at-risk patients and referrals to financial support services may help lessen this concern. At the state level, efforts to manage the escalating cost of cancer treatment, provision of better financial coverage and support and addressing the aspect of unemployment of cancer patients would be needed.

Fatigue was the most prevalent physical concern and one of the predictors for QOL in this study. Cancer-related fatigue is a well-established concern for cancer survivors [8, 38, 41, 42, 52]. Fatigue reduces QOL by affecting a patient’s self-concept, appetite, activities of daily living, employment, social relationships and compliance with medical treatment [8, 18, 41, 52], and may lead to treatment discontinuation and reduced survival [53]. Our study also found that fatigue was a major concern of the longer-term cancer survivors which suggested that fatigue might have some lingering effect after cancer treatment. Bower’s [53] review suggests that approximately slightly more than a quarter of cancer survivors experienced persistent fatigue through 10 years after cancer diagnosis and that it was underreported by patients and undertreated by clinicians. Besides fatigue, our study also found that patients who had physical concerns of pain had poorer QOL. In addition, one of the risk factors for having ≥ 1 physical concern was whether patient had chemotherapy. Our findings are consistent with other studies. For instance, Heydarnejad et al. [18] found that QOL of patients undergoing chemotherapy was lower in patients with pain than to those who had no pain and pain was found to be the strongest predictor of fatigue, Fatigue can be caused by pain [52]. This may potentially reveal a symptom cluster (i.e., two or more concurrent symptoms that are related and may or may not have a common cause) [54] that warrants more in-depth study to closely examine if there is any relationship between these symptoms. Knowledge of whether these symptoms are interrelated within a cluster might therefore help manage these symptoms more effectively and thus lessen the total symptom burden.

Significant difference in QOL was also found between patients who were concerned with the most prevalent issue and those who were not for the NT and RS patients, but not the CT patients. It is not surprising that NT and RS patients’ QOL is more significantly affected as these are vulnerable times in the survivorship trajectory and the psychological distress confronting them is well reported in the literature [4, 55, 56].

Based on current evidence, cancer treatment with its inherent side effects and whether it is efficacious, FOR, financial concerns and fatigue are the most distressing concerns with some of these concerns affecting their QOL in cancer patients throughout their cancer trajectory. These concerns warrant the monitoring of these acute and long-term effects across the entire cancer trajectory for clinical identification of patients who might benefit from enhanced medical attention resulting in an improved QOL. They also underscore the importance of creating an information and supportive care environment that addresses survivors’ information needs and emotional support over time. This could also include assessments for symptoms and distress, and the adoption of the use of survivorship care plans (SCPs) [57, 58]. SCPs have been recommended by the IOM [59] as a tool to assist cancer survivors’ transition from cancer treatment to follow-up care through educating survivors and providers with comprehensive health information and resources [58]. This would also potentially address their concern about the integration of survivorship care between oncology and primary care settings. This is critical as well informed and supported patients have been associated with many positive outcomes, including, increased patient involvement in decision making, increased satisfaction with treatment decisions, enhanced coping during the diagnostic, treatment and post treatment phases of illness, decreased anxiety and mood disturbances, and less emotional distress [22, 23, 27, 60, 61].

5. Limitations

There are several limitations in this cross-sectional survey, which collected data on the perceived concerns from a selective group of cancer survivors at a specific point in time in their survivorship trajectory using a non-validated questionnaire for the study population. Longitudinal studies of cancer survivors’ needs and their concerns throughout their survivorship trajectory would provide more complete insights on the changes in concerns at different times in the continuum of care. Identifying the ongoing and changing concerns of cancer survivors especially as they transit away from the treatment phase remains a key challenge for survivorship study. To partly overcome this limitation, we analysed the survey data according to key time points of cancer survivorship such as during treatment, treatment completion and recurrence instead of variable such as time since cancer diagnosis.

The study sample included only patients diagnosed with colorectal, breast, lung, gynaecological, prostate or liver cancer from a single cancer centre, and this might limit the generalization of the results to other settings. Data on non-respondents were also not systematically collected and as such, the participants may not be representative of the general population of cancer survivors. In addition, QOL was measured using a 0-10 scoring scale in this survey, similar to the QOL question asked in the original questionnaire from the Mayo clinic. While the 0-10 scoring scale provided a consistent method to measure QOL across the various groups of cancer survivors, this scale may not be the best measurement of a latent variable such as QOL. Given these, the results from this survey must be interpreted with caution. There were also proportionately more breast cancer survivors who participated in the survey, which suggested that the data might underrepresent the concerns of cancer survivors with the other cancer types. To limit these effects, we reported the survey results based on the overall cohort and by cancer survivorship stages instead of breaking down the analyses by cancer sites.

In spite of these limitations, given the large sample of the top 6 most common cancers in Singapore, we believe that our study has added valuable insights on the concerns of cancer survivors treated in an Asian cancer centre. It also helped prioritized which are the concerns that should be the focus of prevention and remediation efforts in our patient care delivery.

6. Conclusion

The study concludes that cancer survivors in Singapore face multiple challenges and had various concerns at various stages of cancer survivorship, some of which negatively affect their QOL. As better-informed patients are more able to cope, more satisfied with their care and do better clinically, it is critical that sufficient resources be allocated to develop appropriate strategies to address the key areas of concerns of cancer survivors. Important areas to address include symptom assessments and management, adoption of distress screening tools at each transition of survivorship trajectory, and development of education materials and psychosocial support services relating to the various identified concerns so as to enhance coping skills and improve their QOL, with the main ones being the long-term effects of cancer treatment, risks of cancer recurrence, fatigue, and financial support and resources.

Another strategy worth considering is the adoption of the SCPs which is highly recommended by the IOM. Such care plans could potentially enable the survivors to play an active role in the management of long-term effects of their cancers and provide an effective communication tool for their primary healthcare providers to provide appropriate care to these survivors. Finally, a periodic audit of the concerns of survivors and how well their needs are met should be conducted under a patient-centered approach in understanding and addressing the unique and evolving concerns of cancer survivors across the survivorship trajectory.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Centre Research Fund (NCCRF-YR2016-JUL-PG3). We express appreciation to the patients who participated in this research. Special thanks to nurses and clerical staff for their invaluable contributions. Appreciation is also extended to Ms May Jin Chew for the administrative support rendered.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical consent was obtained from the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board (CIRB) prior to the study. Waiver of written informed consent was obtained as no personal identifiers of respondents were obtained.

Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Source of Support

This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Centre Research Fund (NCCRF-YR2016-JUL-PG3).

Author Contributions

GPC conceptualised and designed the study. Data collection was managed by GPC. WSO performed data cleaning and statistical analysis. QSN and HKT supervised and provided guidance and expertise. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Stein KD, Syrjala KL, Andrykowski MA. Physical and psychological long-term and late effects of cancer. Cancer Supplement 112 (2008): 2577-2592.

- National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (NCCS). Our Mission. NCCS (2008).

- Chan HK, Ismail S. Side effects of chemotherapy among cancer patients in a Malaysian General Hospital: experiences, perceptions and information needs from clinical pharmacists. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15 (2014): 5305-5309.

- Farpour HR, Habibi L, Owji SH. Positive impact of social media use on depression in cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 18 (2017): 2985-2988.

- Pearce A, Haas M, Viney R, et al. Incidence and severity of self-reported chemotherapy side effects in routine care: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 12 (2017): 1-12.

- Solheim TS, Blum D, Fayers PM, et al. Weight loss, appetite loss and food intake in cancer patients with cancer cachexia: three peas in a pod? - analysis from a multicentre cross sectional study. Acta Oncologica 53 (2014): 539-546.

- Trill MD. Psychological aspects of depression in cancer patients: an update. Annals of Oncology 23 (2012): 302-305.

- Kuhnt S, Ernst J, Singer S, et al. Fatigue in cancer survivors-prevalence and correlates. Onkologie 32 (2009): 312-317.

- Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, et al. Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioural health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 104 (2012): 386-405.

- Kim YA, Yun YH, Chang YJ, et al. Employment status and work-related difficulties in lung cancer survivors compared with the general population. Annals of Surgery 259 (2014): 569-575.

- Ochayon L, Zelker R, Kaduri L, et al. Relationship between severity of symptoms and quality of life in patients with breast cancer receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy. Oncology Nursing Forum 37 (2010): 349-358.

- Yang P, Cheville AL, Wampfler, et al. Quality of life and symptom burden among long-term lung cancer survivors. J Thorac Oncol 7 (2012): 64-70.

- Zucca AC, Boyes AW, Linden W, et al. All's well that ends well? Quality of life and physical symptom clusters in long-term cancer survivors across cancer types. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 43 (2012): 720-731.

- Tan ASL, Nagler RH, Hornik RC, et al. Evolving information needs among colon, breast, and prostate cancer survivors: results from a longitudinal mixed-effects analysis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prev 24 (2015): 1071-178.

- Wilson SE, Anderson MR, Meischke H. Meeting the needs of rural breast cancer survivors: what still needs to be done? Journal of Women’s Health and Gender-Based Medicine 9 (2000): 667.

- Kale HP, Carroll NV. Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 122 (2016): 1283-1289.

- World Health Organisation (WHO). WHOQOL: Measuring quality of life. WHO (2019).

- Heydarnejad MS, Dehkordi H, Dehkordi SK. Factors affecting quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. African Health Sciences 11 (2011): 266-270.

- Avis NE, Crawford S, Manuel J. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23 (2005): 3324-3330.

- Yun YH, Kim YA, Sim JA, et al. Prognostic value of quality of life score in disease-free survivors of surgically-treated lung cancer. BMC Cancer 16 (2016): 505.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Patient-centered communication and shared decision making. In Eds.: Levit LA, Balogh EP, Nass SJ, et al. Delivering High-Quality of Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for A System in Crisis. Washington: The National Academies Press (2013).

- Hesse BW, Arora NK, Beckjord EB, et al. Information support for cancer survivors. Cancer Supplement 112 (2008): 2529-2540.

- Husson O, Mols F, van de Poll-Franse LV. The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 22 (2011): 761-772.

- Principle causes of death. Ministry of Health (MOH) (2018).

- Mollica M, Nemeth L. Transition from patient to survivor in African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 38 (2015): 16-22.

- Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, et al. Breast cancer survivors' supportive care needs 2-10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 15 (2007): 515-523.

- Miyashita M, Ohno S, Kataoka A, et al. Unmet informational needs and quality of life in young breast cancer survivors in Japan. Cancer Nurs 38 (2015): 1-11.

- Hauken MA, Larsen TMB, Holsen I. Meeting reality: young adult cancer survivors' experiences of reentering everyday life after cancer treatment. Cancer Nurs 36 (2013): 17-26.

- Stanton AL, Rowland JH, Ganz PA. Life after diagnosis and treatment of cancer in adulthood: contributions from psychosocial oncology research. American Psychologist 70 (2015): 159-174.

- Zebrack B. Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 17 (2009): 349-357.

- Director’s message. National Cancer Centre Singapore (2017).

- Cancer Survivors Survey of Needs. Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (2016).

- SAS: Analytics, Artificial Intelligence and Data Management. SAS Institute Inc. SAS version 9.4 (2018).

- Department of Statistics Singapore. Death and life expectancy (2018).

- Singapore cancer registry annual registry report 2015. National Registry of Diseases Office (NRDO) (2017).

- Pan HC, Gray R, Braybrooke J, et al. 20-year risks of breast-cancer recurrence after stopping endocrine therapy at 5 years. N Engl J Med 377 (2012): 1836-1856.

- Cupit-Link M, Syrjala KL, Hashmi SK. Damocles’ syndrome revisited: update on the fear of cancer recurrence in the complex world of today’s treatments and survivorship. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 11 (2018): 129-134.

- Cutshall SM, Cha SS, Ness SM, et al. Symptom burden and integrative medicine in cancer survivorship. Support Care Cancer 23 (2015): 2989-2994.

- Koch L, Jansen L, Brenner H, et al. Fear of recurrence and disease progression in long-term (≥5 years) cancer survivors-a systematic review of quantitative studies. Psycho-Oncology 22 (2013): 1-11.

- Mazanec SR, Gallagher P, Miano WR, et al. Comprehensive assessment of cancer survivors’ concerns to inform program development. JCSO 15 (2017): 155-162.

- Ness S, Kokal J, Fee-Schroeder K, et al. Concerns across the survivorship trajectory: results from a survey of cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum 40 (2013): 35-42.

- Stanton M, Franco G, Scoggins R. Case management needs of older and elderly cancer survivors. Professional Case Management 17 (2011): 61-69.

- Jimenez RB, Perez GK, Rabin J, et al. Fear of recurrence among cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 35 (2017): 10053.

- Sarkar S, Scherwath A, Schirmer L, et al. Fear of recurrence and its impact on quality of life in patients with hematological cancers in the course of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 49 (2014): 1217-1222.

- Kim Y, Carver CS, Spillers RL, et al. Dyadic effects of fear of recurrence on the quality of life of cancer survivors and their caregivers. Qual Life Res 21 (2012): 517-525.

- Petzel MQB, Parker NH, Valentine AD, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and quality of life among survivors of pancreatic and periampullary neoplasms. Journal of Clinical Oncology 30 (2012): 289.

- Cho D, Park CL. Moderating effects of perceived growth on the association between fear of cancer recurrence and health-related quality of life among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 35 (2017): 148-165.

- Sherwood PR, Donovan HS, Rosenzweig M, et al. A house of cards: the impact of treatment costs on women with breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Nurs 31 (2008): 470-477.

- Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, et al. A composite measure of personal financial burden among patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Medical Care 52 (2014): 957-962.

- Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. Journal of Oncology Practice 10 (2014): 332-338.

- Sharp L, Carsin AE, Timmons A. Association between cancer-related financial stress and strain and psychological well-being among individuals living with cancer. Psycho-Oncology 22 (2013): 745-755.

- Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, et al. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology 18 (2000): 743-753.

- Bower JE. Cancer-related fatigue-mechanisms, risk factors, and treatments. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 11 (2014): 597-609.

- Fan G, Filipczak L, Chow E. Symptom clusters in cancer patients: a review of literature. Current Oncology 14 (2007): 173-179.

- Katowa-Mukwato P, Lonia M, Margaret MC, et al. Stress and coping with cervical cancer by patients: a qualitative inquiry. In J Psychol Couns 7 (2015): 94-105.

- Kushwaha GS. A study of seeking guidance and support coping strategy of cancer patients. Int J Psychol Couns 6 (2014): 66-73.

- Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Edu 28 (2013): 290-296.

- van de Poll-Franse LV, Nicolaije KAH, Ezendam NPM. The impact of cancer survivorship care plans on patient and health care provider outcomes: a current perspective. Acta Oncologica 56 (2017): 134-138.

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington: The National Academies Press (2006).

- Li PWC, So WKW, Fong DYT, et al. The information needs of breast cancer patients in Hong Kong and their levels of satisfaction with the provision of information. Cancer Nurs 34 (2011): 49-57.

- Lo AC, Olson R, Feldman-Stewart D, et al. A patient-centered approach to evaluate the information needs of women with ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Clin Oncol 40 (2017): 574-581.

Impact Factor: * 4.1

Impact Factor: * 4.1 CiteScore: 2.9

CiteScore: 2.9  Acceptance Rate: 11.01%

Acceptance Rate: 11.01%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks